Adventure Camera Man

How did it all start? Was it your childhood dream to become an adventure cameraman?

Well, I'm not sure that anyone really knows what they want to do in their future lives. I certainly didn't. But adventures exist all around us, no matter where. As a young lad, I would love to jump on my bike and explore the quiet countryside of North Norfolk; but I never dreamt that those times would lead to a life of filming adventures.

I was going to head to university to study geology after finishing school, but things didn't work out. At the age of 18 I felt things crumble.... my exam results made for less than encouraging reading. The idea of re-sits made me sick. I ended up working in a factory that made pressure sensing switches for showers, feeling what intelligence I had being replaced with the fog of an automaton. Then one Friday there was a job advert in a local paper for Trainee Technicians at the BBC. The reason my studies had been such a failure is that I was spending all my time DJing, running a disco business, where me and my friend Simon had designed and built much of the gear, with help from our dads. Studying was far less fun. My other passion was in stills photography. On looking at the application form, with my extra-curricular activities I ticked all the BBC boxes and landed the job.

So, as a school-leaver, I began my career in film and television. I was soon seconded to the studios in Newcastle, where a fledgling interest in climbing grew into an all-consuming passion. The mountains were in such striking contrast to the flat, idyllic landscape in which I had grown up, and those peaks were now within easy reach. I was hooked. I read the books, bought the maps, learned how to use a rope, and wondered what if.... So, after 6 years I just resigned from the BBC to follow a pipe-dream to combine mountaineering and filmmaking.

The day I handed in that letter to my boss, I went over to the Lake District to blow away the steam of weeks of deliberating my future. At close of play, my good friend James and I ended up in a climbing shop, gazing at the shiny paraphernalia of the modern climber. Beside the rain-streaked glass door there was a notice board with a scrap of paper, hand-written in blue biro.... 'Anyone fancy a winter expedition to Iceland? Give me a call. Paul Walker' and a phone number. I called him.

The night I returned to Newcastle I was heading to meet up with my old BBC colleagues and bumped into a producer, Richard Else, who I knew of but had never really had any dealings with before. He looked at my haggard face, wild, untamed hair, and sun-blistered lips. "I'd heard you'd left. What on earth have you been doing with yourself? By the way you look like ****!"

I told him of our expedition and literally his next sentence was to ask if I wanted to go film with him in the Himalaya that Autumn, with mountaineering legend Chris Bonington. I almost bit his hand off. From 1990 I haven't really looked back.

For me, adventure filmmaking has come about in an organic way through happenstance that was fuelled by a deep passion for the wild places and by grasping those opportunities when they arise.

When filming in remote and sometimes treacherous areas, how do you and your team work together to navigate and stay on track?

In many of the film locations we find ourselves in, the complexity of the terrain seems to outstrip the level to which the ground has been surveyed; this renders many of the available maps less than ideal. So, we definitely stick together, which is sometimes easier said than done, especially in dense rain-forest. Stop to retie a lace and you disappear in an instant.

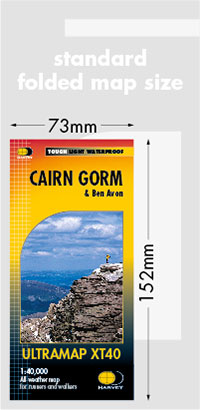

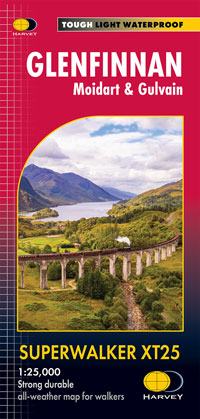

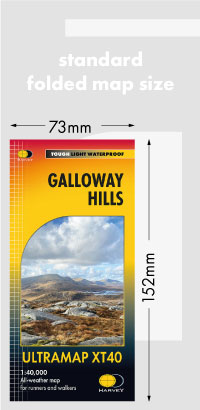

Of course, modern devices also play their part. We are fortunate enough to have GPS, Google Earth and even mobile phones to help us find our way, although I must say that there is no real substitute for a decent paper map for planning, drawing on and providing an overall image of the ground. A paper map doesn't run out of battery. Working within our teams in these remote areas, we have as many tools as possible at our disposal and, hopefully, the skills to use them effectively.

From the outside looking in, your work involves a lot of living life on the edge, sometimes literally. Do you find the work that you do is risky or dangerous?

I'm not going to lie, there is often risk on these filming adventures, but it is part and parcel of the game. Natural environments are infinitely more powerful than we will ever be and so it is best to respect where we are and just who we are. All of us have our physical, mental, and emotional limits, and, while it's good to stretch them and reset where those limits are perceived to be, it's also easy to push into that zone of misadventure. Negativity, and even trauma, can overtake those positive aspects of treading the razor's edge of true adventure.

Who or what is your main inspiration? What keeps you coming back to take on new filming projects?

This boils down to two major things; being a part of a close-knit group of people all pulling in the same direction, and the fact that we live within an infinitely varied, wildly fascinating and spectacular planet. Each film project brings a set of unique and dynamic challenges, where creativity swirls with the physical, technical, environmental, and personal aspects of adventure. Plus, it's about as much fun as being a kid in a sweet-shop and toy-shop combined. It's a privilege to spend time with experts in the field, whether they are indigenous people, scientists or adventurers.

You seem like you are always on the go with new projects constantly in the pipeline, so what do you do for your well-being?

I love being out on my road-bike cruising the quiet roads around Stirling and Perthshire. I suppose it takes me back to my childhood in Norfolk. I also love being out in the Highlands, walking, scrambling, climbing, mountain-biking, and skiing. It feels very different to when I'm working and it's always best with family and friends, having a blether and a laugh.

Well I suppose it has to be either hiking up to the beautiful summit of Ben A'an or getting our dynamic duo of mountain-bikers to make it through the ford. There were a number of 'soggy' failed attempts, but they weren't about to give up.

Ben A'an, despite not being a particularly lofty summit, makes up for it with its spectacular views over Loch Katrine even on a grey and blustery day. Holly, Adam and Chris made light work of the ascent although discussions about who was perspiring the most did get a little hot under the collar.

It was really fun to make the map a character by embedding a 360 camera within its folds. I also wanted to use this kind of image trickery sparingly.

In reality, it was a wonderfully fun project to create, with the 3-way vertical split-screen, images to fit, a flow to create with the map's journey and graphics to overlay. Seeing these things come together is always a treat.

You run the Adventure Filming Workshop and Masterclass programmes at Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Canada. Who would you say is the most interesting person you've met at one of your workshops?

The Adventure Filmmakers Workshop and the Masterclass (part of the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival) in Canada bring together groups of talented filmmakers who are looking to hone their craft, and I've always loved the vibrant mix of people and the energy they all bring to the courses.

It's impossible to call out any one person in particular. The reward comes when they pitch or discuss their film ideas throughout the days and the following year, or a couple of years down the line; they not only have brought that idea to fruition but have become a film finalist at the festival or even an award winner. For one of the recent festivals, 13% of the films screened in the festival had been produced by people who had come through the workshops. It's a superb opportunity and many have gone onto great things, with successful careers with the likes of Red Bull TV and National Geographic or their own independent productions.

Whilst in Canada, I imagine you take great advantage of having such beautiful scenery and mountains nearby. Do you feel like there is a landscape in Canada that is similar to Scotland, or somewhere that reminds you of home?

Over the years I've spent a huge amount of time in the mountains of Canada - as part of the film workshops, on filming expeditions and on personal biking and climbing trips. While the landscape there is a similar mix of mountain, lakes, rivers, and forest it is on a much bigger scale to Scotland and that certainly took a bit of getting used to. But the Rockies, like all other mountain areas around the world, seem to provide brilliant opportunities for a warm welcome. I fondly recall hiking with a pack loaded with climbing kit, sleeping stuff and a few days-worth of food up to the stone-built Abbott Pass Hut perched on the col above Lake Louise. From there, my wife, Andrea, and I climbed the West Face of Mount Lefroy, with its wildly corniced summit ridge. On our descent a couple of female climbers were front-pointing their way up towards us. The goggle and balaclava clad lead-climber stopped level with me and asked, "Excuse me, but aren't you Keith Partridge?" It turned out to be Karen McNeill, a kiwi climber who'd served us in a coffeehouse in Canmore, not far from the Rockies hub of Banff, a couple of years earlier and after chatting we'd arranged to have a grand adventure on the Big Sister the next day. That was to have been the first summit of many in the Rockies and then to randomly bump into her on Mt. Lefroy was a real treat. Back in the hut that night we chatted and laughed for hours, fending off the chill wind that whistled round the rough-hewn walls.

That kind of chance meeting seems to happen more and more as we become further immersed in the mountain community, and it reminds me of all those deep, and, of course, sometimes fleeting, friendships made over the years in Scotland while staying in climbing huts and bothies. So, I think it's more that mountain landscapes of Canada, Scotland or wherever deliver shared experiences that run deep in the memory.

Sadly, Karen went missing and was never found while climbing a remote line on Mount Foraker in Alaska.

Way back, I was on a solo trip trying to bag all the Munros around Loch Mullardoch and Glen Affric. It was February and I intended to bivouac on the ridges whatever the weather. I'd planned the route meticulously to take in all the subsidiary summits, with a route card now sealed with my map in its case. My first night out was a delight, lying beside the summit of Carn nan Gobhar with starlight and purring stove. The following morning when I wriggled upright in my biv-bag I found the cloud-base had dropped considerably and the wind was increasing. I was totally reliant on the map, compass, and timings. Things progressed well, on target and on schedule, until I was near Toll Creagach, above Affric, and I found myself barely able to stand in what had become a violent blizzard. It was beyond the gloom of dusk, and I decided to burrow in the drifts behind a large boulder, compressing the snow to make balls and build a rudimentary shelter - half cave, half igloo.

The following morning conditions were still wild. I reconciled myself to another day with the map and compass.

Out of everything you've accomplished so far, from delving into the depths of glaciers, to delivering an Olympic Gold Medal to the summit of Mount Everest, what would you say is your career highlight?

Career highlight? That's tricky. There are so many memorable moments and highlights.

Certainly, the iconic 'Touching the Void'. It's a film that, as the specialist mountain cameraman, I've always been thrilled to have been involved with. Hunting with Golden Eagles in Mongolia, and the other stories for the BBC's Human Planet series, were a privilege to shoot, and gave all of us windows into the lives of the most incredible people living in some of the harshest environments on Earth.

Reaching the summit of Everest in 2012 was a challenge and I could add that getting back down was an even bigger one. Certainly memorable, that expedition needs a whole blog to itself.

Writing my book 'The Adventure Game' and seeing it launch at the Edinburgh International Book Festival was a thrill. There is something very special about walking past a bookshop window and seeing your professional life in print. I could go on!

Images © Keith Partridge

Return to the News & Features Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch