November 2021 - Decision Making

by Nigel Williams

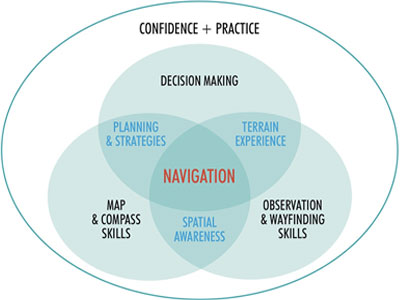

This decision making element highlights the difference between much of the traditional classroom based map reading tuition and on the ground navigation teaching. Consequences make the latter process real, and develops the cognitive pathways that our brains constructed millennia ago before maps were invented. This is often referred to as wayfinding skills and requires development of spatial awareness and terrain confidence.

Teaching and learning map and compass skills is relatively easy. It is all the other bits that go into "navigation" that are more difficult and really have to be done outdoors on the ground.

When walking in a new area, information is key to decision making. The more available information we can accumulate the better the decision is likely to be. Information primarily comes from observation and anticipation. Spending 2/3rds of the time looking at the terrain 360º around and only 1/3rd looking at the map is a good measure of where our attention should be. We can memorise a bit of map often at a glance.

Keep the map easily to hand and regularly cross reference ground to map and map to ground, including crucially, the interpretation of the 3rd dimension - contours and land shape which often provides about a third of our available information, but is so often overlooked in the decision making process. Keeping the map set when we do this is the most fundamental practical skill and essential to interpreting what we see and making route choice decisions.

With on line mapping one can plan a route at home and investigate open source mapping and satellite images to help anticipate what might be some visible, key landscape features.

Developing an awareness of time and distance is a great help. Questioning if it is going to be 10 or 20 minutes to the junction potentially helps us to disregard a path that appears within 5 minutes. Pacing can on occasions be used as well.

Focusing on the navigation is not easy. There are a number of things that inhibit the process. In unfamiliar surroundings we are often admiring the scenery, enjoying the environment and watching our feet as opposed to checking what we see on the map.

There are a lot of distractions and multi tasking going on especially when in a group. How often have we walked deep in conversation and then stopped and questioned ourselves as to whether we have passed a particular landmark or turning we needed to take?

More confident navigators are often tempted to take short cuts across country to cut off a corner just using a rough belief in their sense of direction instead of getting the compass out and just checking their direction accurately.

There are also the human traits often referred to as "heuristic biases", such as being drawn to details that confirm our own existing beliefs. In other words trying to fit the map to the ground, assuming someone else is doing the navigating or relying on the person believed to be the most experienced, following people ahead of us, assuming they are going the same way as us (and eventually realising they are not) or choosing what looks like the easiest path option when we are tired.

When navigating off the path in poor weather or complex terrain, route planning and choosing the appropriate navigation strategy are further critical decision making elements.

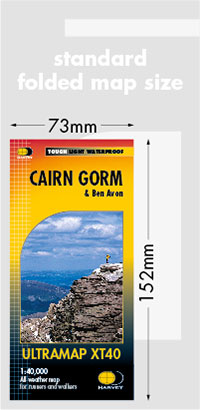

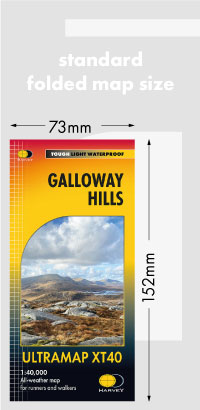

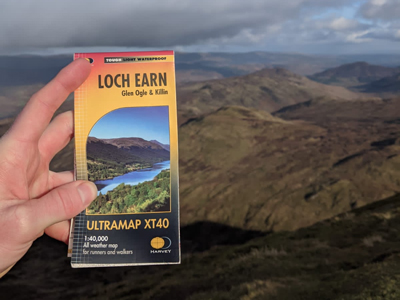

HARVEY Ultramaps really make this easy when in the hills. If it is a faff to get the map out and unfold it we probably won't bother, which naturally impacts our navigation and relocation strategy, which of course is likely to be our weakest and least confident skill.

Learn more about HARVEY Ultramaps

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch