Orienteering maps and navigation

by Nigel Williams

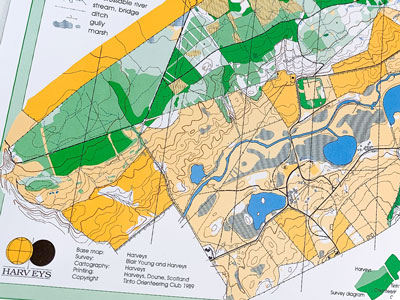

The scale, generally 1cm on the map = 100m on the ground (1:10,000), means that most of what we see around us is marked on the map. The maps usually cover well-walked and sheltered areas and one is rarely more than a few kilometres from a car. This reduces the risk of becoming lost, concerns regarding fitness, changing weather and what to carry and also time pressures.

I find that the walking/mountaineering world seems remarkably sceptical about using orienteering maps for teaching navigation. They are very quick to point out that orienteering is a running sport and that isn't what hillwalkers do. However, I'm not talking about attending orienteering events, good though it can be. This is about using the orienteering map as a tool for teaching and practising navigation. Navigation is fundamentally planning and decision-making, regardless of the map scale, environment or activity in which we deploy the skills. In essence, the orienteering map miniaturises the terrain and offers a range of difficulty enabling lots of individual skills practice at an appropriate level, with little consequence when mistakes are made, thus building navigation and decision-making confidence.

It is interesting that outdoor people - instructors and participants - have embraced artificial miniaturisation for nearly 50 years to help develop and practice skills to participate in the activity in its true environment, avoiding the issues of consequences, remoteness, time pressures, etc. Indoor climbing and dry-tooling walls, bike and pump tracks, dry and indoor ski slopes, roller skiing tracks, artificial white water courses etc. But there is still a reluctance to try navigation with an orienteering map, perhaps due to lack of familiarity.

To quote Matthew Syed, in his book Black Box Thinking, "Enlightened training environments maximise the quantity and quality of feedback, thus increasing the speed of adaptation".

As I said at the start, the availability of orienteering maps is a game changer. British Orienteering now have a website - www.goorienteering.org.uk - listing well over 700 maps for permanent and virtual orienteering courses around the UK. These can be purchased and downloaded for a couple of pounds through the website, some are free to download and for others you are directed to the local tourist or countryside rangers' office to purchase them.

All we need to do is walk and navigate with the map, choosing our own objectives or using ones marked for the permanent courses, which are usually wooden posts with a code on or a QR code plate.

An orienteering map is a valuable tool for the teaching and practice of every navigation skill. Learning to navigate requires progressions in terrain, observation and spatial awareness, as well as map scales, map and compass skills, all of which contribute to navigation and decision-making confidence.

I suspect that many people started navigating by going through these map scales in reverse and finding much of what they observed close to them was not marked on the 1:50,000 map. When learning most new skills our observation tends to be on things close to us, the ground under our feet, and the tools we are using rather than distant landmarks.

Learning navigation on a 1:50,000 map is not only frustrating but has implications for trust and confidence in the map and also limits the opportunities for repeated practice and feedback of skills. Once disorientated there can be very limited information to relocate with and the consequences of a wrong decision can cost a lot of time, effort and distress. It is easy to see why some people resort to reliance on the GPS, which can come with a whole other set of challenges.

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch